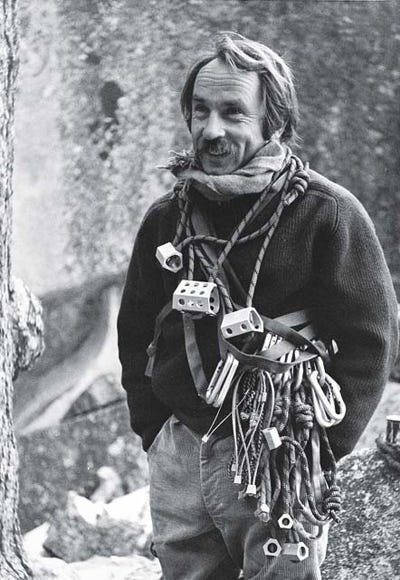

Yvon Chouinard: The Reluctant Billionaire Who Turned Patagonia into a Minimalist Blueprint for Real Sustainability

Yvon Chouinard shows that it is possible to build a global company, stay a dirtbag at heart, and use business as a serious tool for protecting the living planet rather than stripping it.

Yvon Chouinard’s journey from dirtbag climber to Patagonia founder reveals how radical simplicity, “enough” capitalism, and putting Earth as the only shareholder can guide anyone who wants freedom without destroying the planet.

The Dirtbag Who Never Wanted a Company

Before he became “the billionaire who gave his company away,” Yvon Chouinard was just a skinny kid obsessed with cliffs, ocean swells, and wild places. He lived out of a car, slept under the stars, and forged climbing gear in a coal-fired forge so he could afford another season in Yosemite.

He never set out to be a CEO.

He wanted a life rich in freedom, not assets. Very much what we want here at The Rich Minimalist. That tension—between wild freedom and the machinery of business—became the through-line of his life and the DNA of Patagonia.

From Pitons to Clean Climbing

In the 1960s, his steel pitons quietly revolutionized big-wall climbing and made up about 70% of his income. Then he noticed something uncomfortable: every hammered piton scarred the rock, turning his beloved Yosemite cracks into permanent wounds.

Most entrepreneurs would have shrugged. Chouinard did the opposite.

He killed his own golden goose, phased out pitons, and introduced aluminum nuts and “clean climbing” gear that left almost no trace.

There’s a good lesson in this:

When your business model conflicts with your values, you change the model—not the values.

That one decision became a template: The company that he formed, Patagonia, would keep choosing the planet over short-term profit, again and again.

Building a Different Kind of Company

When Patagonia took shape in the 1970s, the goal was simple: make the best gear, cause the least possible harm.

Not “maximize shareholder value.” Not “scale at all costs.” Just high-quality tools for people who loved wild places, made with as little damage as possible to those places.

That philosophy shaped everything:

Materials: early switch to recycled paper, organic cotton, and lower-impact fabrics when the rest of the industry barely knew what “sustainable sourcing” meant.

Repair and reuse: Patagonia normalized repairing clothes, reselling worn gear, and telling customers not to buy a new jacket unless they really needed it.

Culture: flat structures, open offices, and a “let my people go surfing” attitude that treated employees as whole humans, not just resources.

The message was clear:

A company is a living ecosystem, not a money-printing machine.

Minimalism as a Business Strategy

Chouinard liked to say:

“The hardest thing in the world is simplifying your life; it’s easy to make it complex.”

He applied that to gear, operations, and his own lifestyle.

Simplicity meant:

Designing products to be durable, repairable, and timeless instead of chasing fashion cycles.

Trimming everything that didn’t serve the mission—unnecessary SKUs, wasteful marketing, bloated offices.

Living personally with “sufficiency rather than excess,” choosing small homes, hand-me-down cars, and long stretches of surf over luxury.

Minimalism here is not aesthetic. It is a refusal to trade life energy and planetary health for status consumption. For someone pursuing FIRE or a rich minimalist life, Patagonia demonstrates that “less but better” can be a competitive advantage, not a handicap.

Making Earth the Only Shareholder

In 2022, Chouinard and his family made a decision that shook the business world: they effectively gave Patagonia away.

Instead of selling or going public, they transferred ownership to a trust and a nonprofit—Patagonia Purpose Trust and the Holdfast Collective—with one clear mandate:

All profits not reinvested in the business will go to protecting the planet, in perpetuity.

In his open letter he wrote, “Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source… As of now, Earth is our only shareholder.”

Man, I love that!

And it’s not marketing. It is genuine and a structural hack against the default logic of capitalism. He looked at the usual exits—sell to a giant, or IPO—and called them what they were: invitations to compromise everything Patagonia stood for. Then he designed a third, revolutionary path, aligned with his original intent as a climber who just wanted to protect the places he loved.

Real Sustainability, Not Green Theatre

Being sustainable is fashionable. But more often than not, it’s not done for the real reasons it should be done.

Most “sustainable” brands talk about offsetting, recycled packaging, and feel-good campaigns. Basically to look good and comply with the trend without really meaning it.

Chouinard insisted on a more brutal question: Is the world actually better because this company exists?

That led to:

Giving 1% of annual sales to grassroots environmental groups long before ESG was fashionable.

Funding activists who blockade mines, protect rivers, and sue governments, not just plant trees for Instagram.

Publicly acknowledging that any product has a footprint—and asking customers to buy less, use longer, and repair first.

Real sustainability is not guilt-free consumption. It is less consumption, directed with conscience. Because let’s be clear: even the most hardcore minimalist needs to consume something and every Euro spent has some footprint. Chouinard and Patagonia’s view on consumption fits very well with a tiny-house, off-grid, semi-nomad lifestyle: own fewer, better things, keep them longer, and reinvest the saved money and energy into what truly matters.

Lessons For a Rich Minimalist Life

Chouinard’s story is not about becoming another business hero. It is about designing a life—and, if needed, a company—that serves freedom and the planet at the same time. Some distilled lessons:

Let your life dictate your business, not the other way around.

He started with climbing, surfing, and wild landscapes, then built work around that rhythm instead of squeezing life into corporate leftover time. This resonates very deeply with myself.When you discover harm, pivot—even if it’s expensive.

Killing the piton business and promoting clean climbing cost real money, but it preserved the rock, the sport, and his integrity. The same logic applies when your lifestyle, investments, or work clash with your deeper values.Define “enough” clearly.

Chouinard rejected endless growth for its own sake. Giving the company away was a concrete declaration that his family had enough and wanted the surplus to go to climate action. Without an “enough,” you’re stuck in the infinite game of more.Design for durability, not dopamine.

In gear, that means bombproof jackets and fixable zippers. In life, it means relationships, skills, and habits that compound—fitness, curiosity, competence in the wild—rather than constant novelty.Treat the planet as a stakeholder, not a backdrop.

He framed Patagonia’s purpose as “saving our home planet,” then aligned legal structures, supply chains, and profits accordingly. For an individual, that can mean choosing a smaller footprint—tiny house, fewer car rides, low-energy living—but also channeling money and time into regeneration, not just neutrality.Stay a beginner, even at 80+.

Even in his 80s, Chouinard continued to fish, surf, experiment, and stay curious, more interested in wild days than boardrooms. The rich minimalist path is similar: you trade accumulation for aliveness.

Yvon Chouinard’s life is a reminder that a “successful adult” doesn’t have to look like a busy executive with a swollen calendar and three houses. It can look like a weathered climber who still sleeps on friends’ couches, who built a global company almost by accident, and who then handed it back to the Earth because that was the only move consistent with his values.

For anyone pursuing financial freedom, tiny-house living, or a semi-nomadic life in the mountains, his example is a challenge: use money and business as tools for freedom and protection, not extraction—and be willing, when the time comes, to give your best creations away.

Thank you for reading. If you found this story inspiring, subscribe to The Rich Minimalist for more true tales, lessons, and minimalist living insights that nourish body, mind, and spirit.

If you like stories like this, you may also like my previous posts:

Helen Thayer: Walking to the Edge of the World (and Finding Herself)

How Ernest Hemingway Survived Two Plane Crashes in Two Days: Grit, Humor and Lessons for Life

Or just leave a comment or a ❤️